Sportlegis

Dr Despina Mavromati

Sports Law & Arbitration in Lausanne

Dr Despina Mavromati is an attorney with wide experience in contractual, disciplinary, and governance matters related to sport. She has experience as counsel, arbitrator, or expert witness in high-profile arbitral and state court proceedings. Her legal practice is shaped by a longstanding, in-depth knowledge of sports dispute resolution, including her former role as Managing Counsel at the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) and her current roles as CAS arbitrator and UEFA CFCB Appeals Chamber Member.

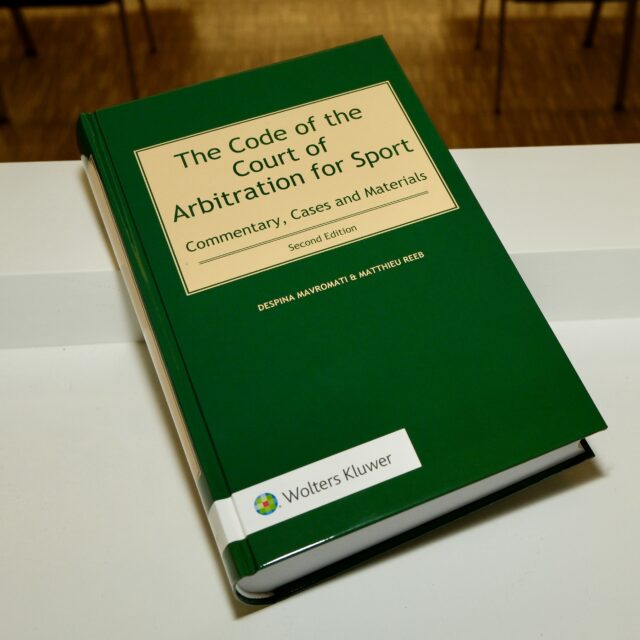

The second edition of the book “The Code of the Court of Arbitration for Sport: Commentary, Cases and Materials (Mavromati & Reeb, Wolters Kluwer, 2025)” has been released. Its first edition, published in 2015, is already a widely cited reference in arbitration practice.

Expertise & Practice AreasLatest Insights

SFT 4A_226/2025: systemic implications – and limited effect – of the Semenya ECHR judgment in sports arbitration

4A_334/2025: Sanctions, Duty of Payment and Limits of the Right to be Heard

International Sports-Related Disputes in 2025 and What to Expect in 2026

Testimonials

Memberships & Affiliations