4A_314 / 2017, Judgment of May 28, 2018

International Motorcycling Federation v. Kuwait Motor Sports Club (Appeal against TAS 2015/O/4316)

This judgment is very interesting—particularly for sports arbitration practitioners. It discusses, reviews and delimits several issues related to the interpretation of an arbitration clause and its interaction with Article 75 Swiss Civil Code for international sports federations based in Switzerland. After shortly reviewing the facts of the cases, this note draws some general remarks on the interpretation of arbitration clauses from the Federal Tribunal judgment.

The Dispute: the right to apply for membership, the jurisdiction of CAS, and the “formal denial of justice”

The dispute initially started between two associations, each wishing to become the sole and legitimate member federation of a country (Kuwait) affiliated to the International Motorcycling Federation (FIM).

The Kuwait Motor Sports Club (KMSC), a non-profit entity of Kuwaiti law, filed a request to become a member of FIM in 2009, despite the fact that the KIAC had been recognized by the FIM as the exclusive member for Kuwait since 1980). The KIAC relaunched its application in both 2011 and 2013.

At the same time, a legal proceeding involving KMSC and KIAC was pending in Kuwait and a decision was rendered in December 2013, recognizing KMSC as the sole entity authorized to organize motorcycle sports in that country (a decision which was subsequently appealed by the KIAC before the Kuwait Court of Cassation and was partially admitted). Following this judgment, KMSC reiterated its request for affiliation to the FIM.

The CAS Award

Several further requests were filed with the FIM, which issued a report but no decision as to KMSC’s membership’s request. Eventually, the KMSC filed a request for arbitration with the CAS.

The KMSC requested to be admitted as the sole FIM member for Kuwait, the exclusion of the other member (KIAC) and compensation for damages by illegally preventing it from joining the FIM.

The CAS Award denied its jurisdiction as to the damages claim only, but admitted its jurisdiction and the claim for the rest. It considered that the lack of decision constituted a denial of justice, ordering the FIM to issue a decision with respect to the parties’ right to be heard.

The important procedural question was whether the KMSC had the right to file a request for arbitration before the CAS against the “lack of decision” by the FIM (or for “formal denial of justice”) according to the FIM applicable rules.

The CAS Panel accepted its jurisdiction, finding that the FIM’s denial to issue a decision constituted a formal denial of justice and therefore a “decision” giving right to an appeal to the CAS (under Article R47 CAS Code) and remanded the matter to the FIM tribunal in order to render a proper decision in this respect.

Appeal to the Swiss Federal Tribunal for alleged lack of jurisdiction

The FIM lodged a motion to set aside the CAS Award, invoking lack of CAS’ jurisdiction (and the violation of ne ultra petita that is also shortly presented below). The pertinent arbitration clause reads as follows: “Any recourse to state tribunals against the final decisions rendered by the adjudicating instances or the General Assembly of the FIM is excluded. Said decisions must be exclusively referred to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) which shall have exclusive authority to impose a rule on the dispute, in accordance with the Code of Arbitration applicable to sport.”

The Appellant (FIM) argued that KMSC was not a FIM member and thus could not invoke the disputed arbitration clause in order to file a claim / appeal with the CAS. It maintained that it could not be inferred, by reading the clause in good faith, that a third party (i.e. not a FIM member) would be subject to the latter clause.

The FIM also supported that there was no formal denial of justice because it had to wait for the pending proceedings before the Kuwaiti state courts to be finalized before rendering a proper decision in this respect. Also, in its view, denial of justice could not apply in private law relationships.

CAS Arbitration and International Federations established as Associations under Swiss law –

Sports Arbitration is “Branchentypisch”

The FIM, like almost all international sports federations, accepts one national federation per nation as its “official” and representative member (under the so-called “Ein-Platz-Prinzip”). Only the official members have voting rights at the FIM General Assembly (GA).

Even though the form of the arbitration agreement must comply with Article 178 para. 1 Private International Law Act (PILA), the Swiss Federal Tribunal has repeatedly expressed its generosity or “latitude” (“bienveillance”) when examining the validity of an arbitration clause, particularly the arbitration clause “by reference” (4A_246/2011 of November 7, 2011 at 2.2.2).

Application of principles of statutory interpretation for large federations of monopolistic nature

When interpreting an arbitration clause included in a federation’s statutes, the method varies according to the type of federation considered. For large federations such as UEFA, FIFA or the IAAF, the SFT applies principles that apply to the interpretation of laws, while for smaller ones, the SFT applies principles that apply to the interpretation of contracts (such as the objective interpretation according to the principle of trust).

No matter what method of interpretation the arbitral tribunal might choose, this can no longer be reviewed by the SFT in a subsequent motion to set aside the award (see also 4A_314/2017 at 2.3.2.1).

Under the principles of statutory interpretation, we apply the literal, systematic, theological and historical interpretation, without a hierarchy between these principles.

Elements in favor of a valid arbitration clause in favor of the CAS

When interpreting the arbitration clause, in favor of validity speak the broad way of formulating the arbitration clause, the exclusion of recourse to ordinary courts (especially when this is made in various parts of the rules of the federation), but also referrals to the CAS Code (which is the procedural regulation of the CAS).

The scope of the arbitration clause is reviewed in view of the decisions included in the arbitration clause (ratione materiae) but also in view of the persons entitled to challenge those decisions (ratione personae).

Jurisdiction ratione personae: Can a non-member rely on the association’s statutes to contest a decision of the association?

If drafted in a less restrictive way than Article 75 CC (which gives the right to contest association’s decisions in principle only to members), the arbitration clause should be deemed to include indirect members or even non-members.

Article 75 CC is an imperative law provision and the parties cannot exclude the control of the decisions of an association by an independent tribunal, either the state courts or the CAS.

Is Article 75 CC applicable only to members of an association?

When there is a valid arbitration clause for an arbitral tribunal in the federation’s statutes, this should apply not only to members but also to non-members which request membership or challenge a decision denying such membership.

This interpretation would favor legal certainty, placing all interested parties on an equal footing as to a possible appeal but also avoid contradictory decisions if, for example, a member goes to CAS and a non-member pursues the state courts, with different review and appeal mechanisms foreseen in each case.

Is the freedom of association unlimited under Swiss law?

How does the principle of autonomy of associations under Swiss law interact with the right of a person / entity to apply for membership and have the possibility to contest the association’s decision before a state court or an arbitral tribunal?

The freedom of the association under Swiss law is not unlimited, particularly for major sports associations of monopolistic character, such as the FIM. Candidate members may also invoke Article 28 CC if suffered an illicit damage to their personality.

Can the lack of decision equate to a denial of justice and thus an “appealable decision” under CAS case law?

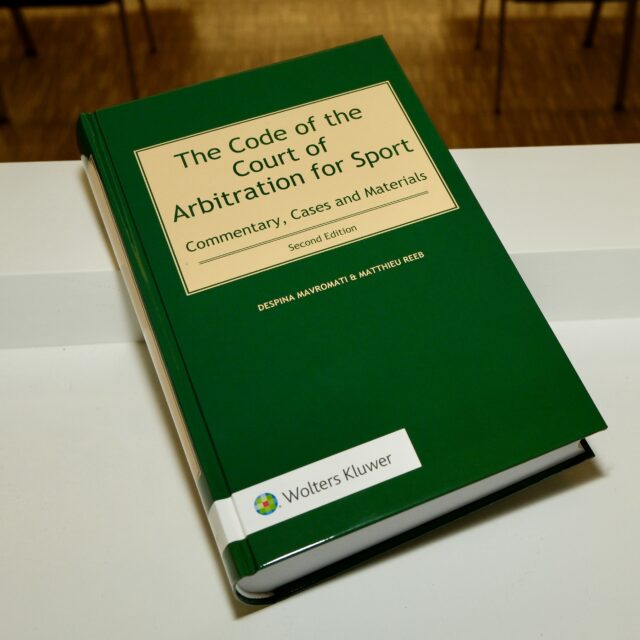

A lack of decision by a competent body extending beyond a reasonable period of time may constitute a denial of justice susceptible of appeal. Citing the CAS commentary (MAVROMATI / REEB, 2015 Wolters Kluwer, n. 23-25 ad art R47 of the Code), the Federal Tribunal has held that “[i]f there is a lacuna in the rules of the sports body regarding cases of inactivity and lack of response to a request, a decision not to open a case or the absence of reaction in general must be considered decision subject to appeal to CAS” (n. 24).

Moreover, “[a] denial of justice should also be affirmed if the first-instance body failed to render a decision within a reasonable period of time” (n. 25). Logically, in these cases it is not required to act within the 21-day appeal period set in Article R49 of the Code.

Does a formal denial of justice exist in legal relationships that emanate exclusively from private law?

The formal denial of justice can also be invoked in a private law relationship and is also possible in arbitration.

Furthermore, it is of little relevance whether the party invoking such denial of justice is an athlete complaining of the inaction of their federation or a national sports association requesting its affiliation to the international federation.

Denial of justice under Swiss administrative law – between the underlying right to a decision and the assessment of an (unjustified) delay

Is the establishment of a formal denial of justice a preliminary question that the SFT can review freely in its control of the jurisdictional objection?

When it comes to plea of denial of justice, there are two aspects under Swiss administrative law: the first presupposes a right to a decision (provided that the decision is subject to appeal); the second is whether there was actual delay and falls within the merits. It can therefore not be reviewed by the Swiss Federal Tribunal.

The existence or not of an unjustified delay will not put into question the jurisdiction of the CAS: it may constitute an element examined by the tribunal when upholding or dismissing the appeal and not an element of admissibility.

Therefore, the question of delay relates to the merits and not to CAS’ jurisdiction and cannot be examined by the Swiss Federal Tribunal within this context.

No violation of Ne Ultra Petita when the Panel reverts the case to the Federation’s tribunal instead of rendering a de novo award as requested by the parties

Under Article 190 (2) (c) PILA, it is possible to attack the award when the panel allocated more or something other than what was requested.

Difference between CAS ordinary and appeal proceedings and ne ultra petita

The power of a CAS panel to revert the case back is explicitly foreseen in CAS appeals proceedings under Article R57 of the CAS Code (and has been accepted by the Swiss Federal Tribunal).

According to CAS practice, the allocation of a procedure to ordinary or appeal proceedings (under Article S20 para. 2 CAS Code) cannot be challenged by the parties as a cause of irregularity.

By the same token, the Federal Tribunal has found that the allocation of a mixed case to the ordinary arbitration procedure cannot reduce the powers of the Panel.

In view of the autonomy of sports federations, the CAS should preferably not substitute itself for the competent organ of a federation in cases where the latter did not render a decision.

Ne ultra petita and principle of good faith

Furthermore, a sports federation would likely violate the principle of good faith by invoking ne ultra petita principle for being asked to render a decision itself instead of being ordered to accept or deny an applicant member. Therefore, a plea of ne ultra petita / extra petita seems hopeless in such a case.